In the 1790s, a medication began to surge in popularity in the United States. Used in tiny doses since the ancient world (and later for syphilis, where it may in fact have had some true efficacy), this new approach required substantially larger doses. Those who used it believed that imbalances within the intestines contributed to most illnesses, and that forcibly expelling the contents of the bowels — purging, generally by means of diarrhea — would restore balance and cure disease. The medication was promoted for children’s teething pain; for yellow fever, cholera, typhoid, and other epidemic diseases; to treat melancholia and other psychiatric conditions; for digestive complaints; and, as a general cure-all. At the height of its use, it was the dominant medicine of the era.

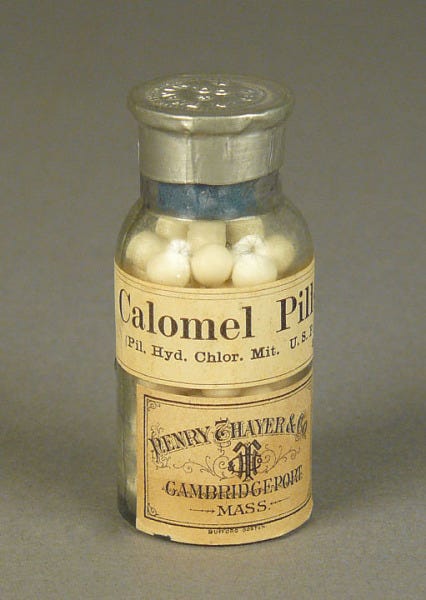

This was Calomel, and there was just one problem: It is a salt of mercury.

Mercury is a heavy metal that is toxic to living organisms. Shiny and silver in color, it is the only metal that is liquid at room temperature. To create a version considered more suitable for medicine, chemists combined the mercury with chlorine to create mercury chloride salts — a white, crystalline powder that could be formed into pills.1

Mercury is toxic because it binds to sulfur-containing proteins in the body, disrupting their normal function. Symptoms of poisoning begin with drooling, tremors, and fatigue, then progress to bleeding gums and tooth loss, personality changes (anxiety, depression, mood swings), difficulty concentrating, memory loss, and kidney damage. At higher exposures, the increasingly severe neurological damage manifests as numbness in the hands and feet, speech difficulties, vision and hearing problems, extreme behavioral changes, kidney failure, and finally, death. The progression was not always linear. In children, effects that were not recognized as mercury poisoning were often described more broadly as developmental delays, seizures, and failure to thrive.

The widespread use of Calomel in the 1850s can make it difficult, looking back today, to figure out whether a given child was born idiotic2, became idiotic after birth, or experienced a combination of congenital and acquired elements.

Take these excerpts from Samuel Howe’s medical notes about idiocy, written in 1846:

“At 4 years of age she had a fever + took much calomel + was very crazy + she nearly died, + did not get so as to walk for 4 or 5 months. Ever since then she has been often weakly...” (Avis Crocker Baker, age 37)

“... it is stated by his friends that he was weak at birth + took calomel, which produced the most violent convulsions...”

(Benjamin Franklin Durrell, age 8)“ ... at one + a half years of age, he was sick with teething + diarrhea, + much dosed with calomel, to solder up his bowels + scrof raw sores with quick silver soft solder...”

(George S Eaton, age 26)“... At one year old he had a scrof. diarrhea + was treated with Calomel to [?] up his bowels; but it salivated him terribly...”

(George Franklin Emerson, age 9)“Idiotic from paralysis + fits at 1-1/2 years of age. The fits were supposed to have been from worms + the use of calomel.”

(William H Kimball, age 13)“From infancy, he has been much doctored with calomel + laudanum, which seem to have stopped the growth of his bones.”

(William Bradley Sturgis, age 16 )

In each of these instances, Calomel complicates — rather than clarifies — the picture. Was there a change in William Sturgis’ growth something that would have emerged regardless? Were William Kimball’s seizures caused by mercury poisoning, or something else?

By 1870, medical purging had dropped out of favor, replaced by the germ theories and scientific medicine that would be more familiar to us today. Even so, mercury in teething powders and other remedies would not be completely banned in the United States until 1948, a full century after Howe and others drew attention to possible links to long-term disability.

For more on the rise and fall of Calomel, check out “Calomel and the American Medical Sects during the Nineteenth Century” by G.B. Rise, available online here.

It bears repeating that the term idiocy, as it was used in the 1850s, is most easily compared to what we call developmental disabilities today, encompassing intellectual disability, portions of the autism spectrum, and other conditions that affected cognitive function. While it certainly held some negative connotations, idiocy was primarily a descriptive term. Those termed idiots were seen as lacking the cognitive capacity to care for themselves. They were also idiotic in a legal sense, for they were considered incapable of entering into contracts and were not legally responsible for their actions. When I use the terms idiocy, idiot, or idiotic in this post, I am referring to that 1850s meaning and not the modern English usage.