Most of what I post online are anecdotes — fun, quirky facts intended to catch the reader’s attention and share my enthusiasm for the stories I come across. Behind the scenes, however, my work is much more serious. My scholarship focuses on the historical experience of intellectual disability, then termed idiocy,1 prior to the 20th century. More specifically, I focus on the experience of idiocy in New England in the early to mid-1800s.

But why? What’s so special about the 1800s?

The timeframe is special because it represents something that has been almost entirely — and intentionally — erased.

If you look for descriptions of intellectual disability in the past, you’ll find one persistent narrative.

Textbooks, websites, and other sources explain over and over again that before our own time, life for individuals with intellectual disabilities in the United States was grim. We are told that such people were outcasts – shunned by their families and by broader society. Into these dark times, the story continues, arrived a generation of upper-class social reformers who would gradually improve conditions for the developmentally disabled nationwide, mostly by creating institutions where none had existed before.

Milton Meltzer’s biography of Samuel Howe is typical of such accounts:

“Sam turned to his new idea. He knew what he was up against. Everyone thought idiotic children were hopeless. You could do nothing for them. The law considered them paupers, but it classed them with rogues and vagabonds, assigning them to the House of Correction when their own families abandoned them. Sometimes these children were put into the State Lunatic Asylum. Everywhere they were so neglected or abused that they sank into a more and more brutish state, going unregretted into early graves."2

Today, this origin story is so widely accepted that nearly all my American readers almost certainly believe some version of it themselves. (Readers in the U.K and European countries have their own similar versions.) It is a powerful story, and one that helps us feel better about ourselves and how we treat each other.3

It is also untrue.

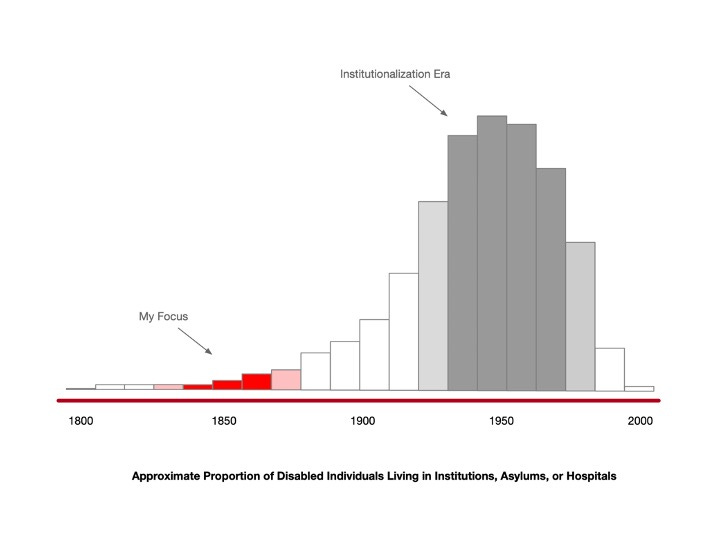

Origin-story versions of disability history are not very old. They came to prominence as part of the institutionalization era, a term that refers to the widespread forced confinement and mistreatment of disabled children and adults from approximately 1900 to 1980. At its height, tens of thousands of individuals across the United States spent their entire lives confined to state-run institutions that were underfunded, overcrowded, and rife with abuse and neglect.

It takes hard work to convince an entire country to put up with something like forced institutionalization, and pseudo-historical accounts were part of that effort. They encouraged a narrative that specifically and intentionally justified institutionalization. While institutions were not perfect, modern writers explained again and again, they were not that bad, for at least they were much better than whatever had come before.

The institutions were not better. They were, in fact, much worse.

Custodial care in institutions marked a dramatic change from the ways those with developmental disabilities had lived in the United States. Before this, family- and community-based care had been the norm. Poverty had terrifying consequences, yes, but it did for anyone without resources, not only those with disabilities. Wealth brought privilege, absolutely, just as it did for anyone fortunate enough to possess it, not only those with disabilities. The lives of individuals with intellectual disabilities were embedded within their families, communities, and wider society.

Families cared. Communities cared. Those with developmental disabilities themselves contributed to both family and community in countless ways. They deserve better than to be demonized in order to create falsely benevolent histories for the same people who would actively hurt other such families and loved ones in the times to come.

And so, we are left with questions:

If everything we think we knew is wrong, how *did* developmentally disabled individuals live in the United States before the eugenics-linked practices of the early 1900s arrived? What was their daily life like, where did they reside, and what roles did they play in their families, communities, and wider society?

Perhaps most importantly, what can we — as we strive to rebuild community-based care — learn from the forgotten families who came before us?

It is these larger questions that I try to answer, one piece at a time.

The term idiocy, as it was used in the 1850s, is most easily compared to what we call developmental disabilities today, encompassing intellectual disability, portions of the autism spectrum, and other conditions that affect cognitive function. While it certainly held some negative connotations, idiocy was primarily a descriptive term. Those termed idiots were seen as lacking the cognitive capacity to care for themselves. They were also idiotic in a legal sense, for they were considered incapable of entering into contracts and were not legally responsible for their actions. When I use the terms idiocy, idiot, or idiotic in this post, I am referring to that 1850s meaning and not the modern English usage.

Meltzer, M. (1964). A Light in the Dark: The Life of Samuel Gridley Howe. Thomas Y. Crowell Co.

Humankind has a tendency to make liberal use of origin myths — powerful stories explaining the past by utterly and completely misrepresenting it. S. K. Green offers a compelling explanation of the phenomenon in his book, “Inventing a Christian America: The Myth of the Religious Founding.”

Naomi, thank you for this introduction to your work. Searching for long-buried stories is a challenge in any circumstance. Your search must be a double challenge, especially since the "institutional story" seems designed to overwrite the community-care stories. Looking forward to hearing more of your discoveries. (We recently watched The Crown episode that featured the sad institutional story of the intellectually disabled nieces of Elizabeth 2's mother.)