The more I do this work, the more I dislike Samuel G. Howe.

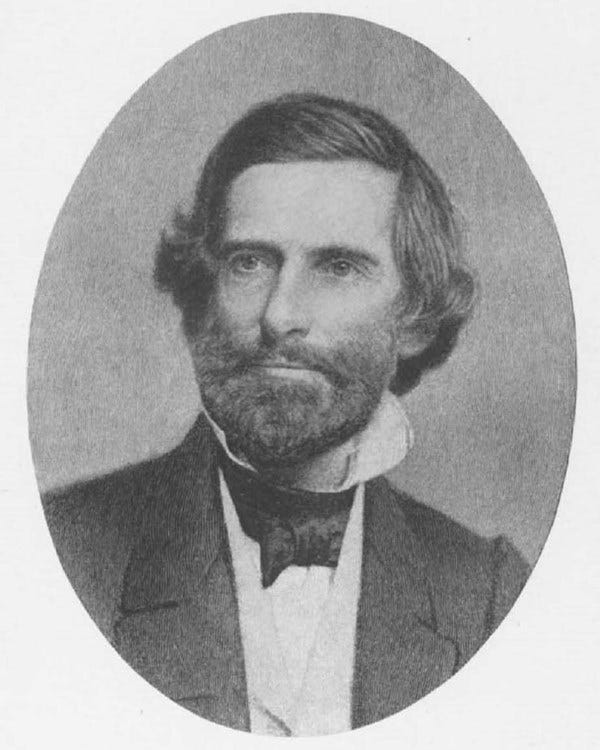

An American physician, educator, and abolitionist, Howe (1801-1876) is the person chosen by history for praise and remembrance in relation to disability education in the 1800s. He is given credit for a great deal of work done by others.

Taking credit is not, in and of itself, a cardinal sin. History has a habit of simplifying storylines by blending many people into one. But Howe was arrogant, sure of his own superiority, and deeply condescending to the families of disabled children, whom he generally painted as incompetent or unfit parents. He believed idiocy1 to be the result of (and therefore, de facto evidence of) immorality and, more specifically, sexual immorality, whether on the part of parents or the children themselves, and he treated families accordingly.2

He also had a habit of simply taking custody of children he felt would be useful pupils (as in, children who might become clear examples of his skill as an educator), and of being quite annoyed if parents were so unreasonable as to stand in his way.

Howe’s description of his first encounters with Abby and Sophia Carter are a good example:

“As we approached the toll-house, and halted to pay the toll, I saw by the roadside two pretty little girls, one about six, the other about eight years old, tidily dressed, and standing hand in hand hard by the toll-house. They had come from their home near by, doubtless to listen, as was their wont, to gossip between the toll-gatherer and the passers-by. On looking more closely, I saw that they were both totally blind. It was a touching and interesting scene -- that of two pretty, graceful, attractive little girls, standing hand in hand, and, though evidently blind, with uplifted faces and listening ears, as if brought providentially to meet messengers sent of God to deliver them out of darkness.”3

Having found these two angels awaiting himself in the role of messenger of God, he set about securing the children. He noted that:

“It would indeed be hard to find, among a thousand children, two better adapted, irrespective of their blindness, for the purpose of commencing our experiment.”

He immediately visited the family and proposed to take charge of the girls. The mother, understandably reluctant to hand her children over to this stranger, is recorded for posterity by Howe as quickly being won over by his sincerity:

“… she soon saw the practicability of the thing, and being satisfied about our honesty, she consented with joy and hope to our proposition of beginning with her two girls, Abby and Sophia Carter. In a few days they were brought to Boston.”

Abby and Sophia would remain in Boston. Despite Howe’s promises that they would receive an education that would lead to greater independence, they would remain at Howe’s school well into adulthood. Howe’s daughter, Laura Richards, would later recall:

“I remember Sophia Carter well, as a comely middle-aged woman, with regular features and side-curls. She was one of the familiar figures of my childhood, the "Institution" being to her, as to many others, a second home.”

Some parents did allow Howe to claim guardianship of their children. Others were less willing to allow it as a long-term arrangement, and, much to Howe’s displeasure, would come to reclaim their child. In 1841, Howe wrote to Horace Mann about such an instance:

To Horace Mann

BOSTON (where else?) July 16, 1841.MY DEAR MANN: -- . . . I have lost my Vermont girl, just as she was beginning to promise finely. Her parents have taken her home; her mother, a very ignorant and very nervous body, conceived a notion that the child would certainly die within a year, and that she should come back and die comfortably at home. She professed, indeed, some dissatisfaction at the child not being treated as Laura is (who is my child and lives with me), but the secret of the whole is she loves her daughter more warmly and blindly than does a cow her calf. She felt, as Scott says of Elspeth, "that to be separated from her offspring was to die."

[…]

Poor thing! I fear they will not bring her back! But it is a great satisfaction to think we broke through the crust, and got at the living spring within: and it is clear we did so.

Ever truly yours,

S. G. HOWE.

The ‘Laura’ whom Howe mentions as his child, was not, in point of fact, his child, either. This is Laura Bridgeman, a deaf-blind girl who was Howe’s showcase pupil for many years. For those not familiar with her life, the book The Imprisoned Guest by Elisabeth Gitter is a great starting point.4

The pattern that emerges is straightforward.

Faced with an insistent Howe, with the possibility that he might indeed be able to give their child something that they could not, and a daunting show of power and privilege, some parents did hand over their children. (Howe was wealthy and politically connected, while most of the families he approached were not). Other families gave in initially but soon refused to continue the arrangement.

Those who refused Howe outright were rare, but did exist. One of my favorite examples comes where you might least expect it — in a family where the power divide was even greater than usual.

Meet Angeline Arms, age 15, visited by Samuel Howe in 1847 in the family home:

“As the brothers + mother had recently taken her off the town, they were afraid of me, + would not let the girl be examined, tho I saw her in the next room + was told that one leg was perished from almost infancy, + that she never could do or say anything nor even walk. Hence I conclude she is of the lowest degree of idiocy; perhaps is even less intelligent than a dog.”

Born in 1831, Angeline was the youngest of five children and significantly disabled from birth. Her father died when she was about ten years old.

Her mother (a widow with young children and no source of support) was evaluated by the town for public assistance, and Angeline, as the household member considered most likely to suffer under the family’s new circumstances, was taken from the family and placed in the Deerfield poorhouse. This was against her family’s wishes. Despite repeated family petitions to bring her home, Angeline remained there a number of years.

There is no record of Angeline’s family officially regaining custody. Rather, it is most likely that in early 1847, when her eldest brother became a legal adult, he simply went and took her home without asking for permission. It is perhaps not surprising, then, that the family viewed Samuel Howe’s visit a few months later with suspicion, and would not cooperate with him.

(There is, incidentally, no evidence to corroborate Howe’s scathing view of Angeline’s likely intelligence.)

Angeline lived to be 57 years old, and lived with family (first with her mother, then the same older brother and his family) for the rest of her life. Her story is a powerful example of the ways the relationships between parents, siblings, and individuals with disabilities could be close, loving, and supportive across socioeconomic circumstances.

It bears repeating that the term idiocy, as it was used in the 1850s, is most easily compared to what we call developmental disabilities today, encompassing intellectual disability, portions of the autism spectrum, and other conditions that affect cognitive function. While it certainly held some negative connotations, idiocy was primarily a descriptive term. Those termed idiots were seen as lacking the cognitive capacity to care for themselves. They were also idiotic in a legal sense, for they were considered incapable of entering into contracts and were not legally responsible for their actions. When I use the terms idiocy, idiot, or idiotic in this post, I am referring to that 1850s meaning and not the modern English usage.

There are a number of instances in Howe’s records where he notes instances of sexual abuse of a child as a cause of idiocy, and does so in a way that suggests that he, at least, considered the child to have some agency in the situation. These are not details that I will be posting about. The children in question never assented to having their experiences detailed to the masses, let alone by an unreliable narrator such as Howe.

Richards, L. E. (1909). Letters and Journals of Samuel Gridley Howe: The Servant of Humanity: Vol. II. Colonial Press.

Howe did have a daughter named Laura, but she was born in 1850, nearly ten years after this letter was written.

Howe sounds like a bit of a narcissist. Unfortunately I think many of the “great minds” of history had such traits, but I don’t recall any of these trying to take and/or keep someone’s disabled child against the parents’ wishes.